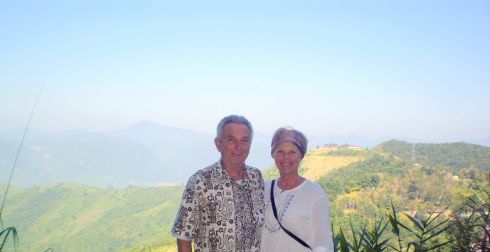

Mrs Chook, with whom I share a home, two dogs, and much of my life, became a widow some considerable time ago, after nursing her husband through lung cancer. For a while she was a member of the local Widows Club. They had good times, played cards and golf, got drunk and raucous, spoke realistically of the men they’d lost, acknowledging their aggravating complexities, at times speaking ill of their dead because there’s no human being who can’t be spoken ill of to some degree, and the Widows Club women were nothing if not honest.

I was once invited to become an honorary member, not because I was widowed but because I was separated, living life without my husband’s daily presence and sharing it with Mrs Chook, but I declined, feeling out of place. Yes, I’d lost my husband in a very real sense, but to see that misadventure as widowhood did not feel true to me.

A separation is indeed a kind of death. But death has different dimensions, and they must be given their due.

I’m sitting in a bus station watching the World Cup on the overhead TV. I’m between worlds, and remembering another bus station, another World Cup on an overhead TV in Cancun, Mexico, another country when I was alone just like now, and it occurs to me that there is something of a pattern in this, bus stations, football, overhead televisions, a heart in a confusion of desire, loss, grief, a woman facing an unknown future. A sense of the complete unknowableness of certain events, transgressive events that tear apart the fabric of the ordinary, events that force open the portal into the extremities of human experience. I realise I have no control over death, or desire or love, and should I attempt to exert any illusionary control I will make myself ludicrous. There are forces abroad in the world that far exceed my puny human capabilities, and there is nothing to be done but ride them out as best I can.

The bus station today is not in Cancun but Sydney, my husband is dying, and I suddenly recall with bizarre accuracy the notice on the door of a hotel room in Mexico City:

Many people are injured having fun in Mexico.

Air pollution in Mexico City is severe.

Failure to pay hotel bills or pay for other services rendered is considered fraud under Mexican Law.

I’m at a loss to understand the workings of my memory until I recall that my journey to Mexico caused my husband great angst, indefinite as I’d announced it would be, determined as I was to go without him as he had travelled so often without me. It marked a turning point in the dynamics between us. I had asserted myself as the leaver rather than the left. Twenty years older than me, he was outraged and bewildered, having spent much of our marriage wishing me to be Penelope, spinning faithfully at my wheel at home and keeping suitors at bay while Odysseus travelled the earth. The role never sat well with me and seemingly out of nowhere I exploded out of it, like a woman blown from the mouth of a cannon. This turning of the tables unhinged my husband somewhat, and he wept at the airport. Not even his tears could melt my determined heart. A woman has to do what a woman has to do I didn’t say, but I could have. These were serious endings. I was no longer who I had been up to that point, and neither was he who had never in his life before wept at an airport, while a woman he loved left him behind.

It is tempting to describe these endings as deaths, but I have a profound distaste for the appropriation of death as a metaphor. There is nothing in life for which death can be asked metaphorically to stand. There is nothing in life that can be likened to the radical absence that is the signifier of death. Death is the one situation in which all hope for presence ends. Up to that point, one has merely endured absence.

I have recently become a legitimate member of the Widows Club, though it no longer exists in its original form. More than three decades of marriage, always unconventional, have ended and I am no longer just living separately from my husband while we continue to love one another in spite of our differences. I am widowed. I have begun the labour of mourning, as Freud described the gradual relinquishing of all hope of connection with the loved one that is made inevitable by his or her death. I will never again see his face. I will never again hold his hand. I will never again climb up on his hospital bed and lay my warm body along the length of his frail and shrunken frame.

It’s the finality that brings me undone. I find myself repeating, in my struggle to come to terms with his departure, I never will again.

In the end, I did not leave him weeping at an airport. He left me. I don’t know if he heard me tell him I will always love him. I don’t know if he heard me tell him he did not have to stay, that I did not begrudge him this journey, that I did not need or want him to remain here with me, that I wanted only his release, that he could leave with my blessing, I don’t know if he heard those things I whispered as I laid my body the length of his, and held his beloved head against my breasts.

Because we’re alive, we inhabit the country of the living; that which is outside, we don’t have the heart to believe, I read, in Hélène Cixious. She’s right I don’t have the heart to believe, yet it is necessary to find the heart to believe, what else is there to do? We live in the house of widows, I tell Mrs Chook, sitting on her bed in my dressing gown, Little Dog lying on my feet, you’re so pale, she says, and I don’t tell her I’ve woken up maybe ten times in the night, crying those tears you know are serious because they are hot, and burn their way down your cold cheeks. We will be all right, she tells me. You will be all right. In time. It takes time.

As is to be expected at the death of a loved one, memories are crowding in on me, our life together parading itself well out of any chronological order, according to some time line I cannot recognise as having anything to do with reality. I see him dancing towards me across our sitting room, singing, You made me love you, I didn’t want to do it, I didn’t want to do it, which always symbolised for me his infuriating reluctance to take responsibility for anything. Give me give me give me give me what I sigh for, you know you’ve got the kind of kisses that I’d die for redeemed him, as he always knew it would. The night before he died I found on YouTube a video of him talking about poetry, made just before his stroke. And then, for reasons I cannot explain, I recalled a scene from The Sopranos in which Meadow Soprano sits beside her unconscious father, crime boss Tony, whom she fears is dying, and reads the Jacques Prevert verse:

Our Father which art in Heaven

Stay there

And we shall stay on earth

Which is sometimes so pretty

I shall stay on earth, which is sometimes so pretty. Vale, Arnold Lawrence Goldman.

Tags: death, Hélène Cixous, Loss, Marriage, The Sopranos, Widows

Recent Comments