Some months ago I wrote here about going to my husband, from whom I’d been separated for some time, after he’d suffered a massive stroke.

With a bizarre assortment of clothes flung distractedly into a bag and no toothbrush, I took the train because all the flights from my part of the world were full.

I had no idea what to expect. He won’t know you, they told me. He doesn’t know anybody. He can’t speak. His right side is paralysed. I’ll come with you, a friend offered, so you don’t have to deal with the shock by yourself.

I accepted her offer. Once I never accepted anybody’s offers of help. I had no idea how to. I knew from early in life how to get through things on my own when there wasn’t any choice. I knew how to trust me, when I couldn’t trust anybody else.

At first, accepting help felt like betraying myself. I confused it with weakness. It wasn’t until I found at the age of 40 that I had cervical cancer and was in serious trouble, that I began to tentatively say, please help me. And everybody did. I’ve not much to feel grateful to that cancer for, but it did cause me to change, and let people love me.

When I walked into A’s room, he was strapped into a wheelchair. I pulled up a chair beside him and took his hand, the one still in working order. He looked at me for a long time, balefully, I thought. I found this look reassuringly familiar. Although he stopped wanting me long before I stopped wanting him, he never seemed to keep that chronology in mind and on the occasions we met after our final separation, acted aggrieved, as if I’d been the one to leg it. Well, I had, but only because I finally understood his desire for me was gone, and how can you stay around for that?

I say desire, which is usually and wrongly understood to be primarily sexual, but I mean it in a much broader sense. He never stopped wanting me sexually, nor I him, but it got to the point where that was all he wanted of me, while I still trembled at the whole of him.

Sometimes I finally get to thinking of the past,

We swore to each other that our love would surely last

I kept right on loving, you went on a fast

Now you are too thin and my love is too vast…*

It was 2006, and I’d been in Mexico for months without him because, on the surface of it, timing. We exchanged dozens of acrimonious emails in which he berated me for going without him, and I hurled back heartbroken accusations to the effect that for more than twenty years he’d only been a tourist in my life when what I’d wanted was a dedicated traveller. He then wrote that he supposed I was fucking some rich Mexican with a hundred-dollar haircut, or maybe I’d gone back to my old ways and was enjoying a senorita in some lesbian resort on the Caribbean coast, to which I replied, too exhausted to try for wit or even something vaguely cutting, what’s it to you, anyway. Leave me alone. I’m not talking to you anymore. A lengthy, angry, miserable silence ensued.

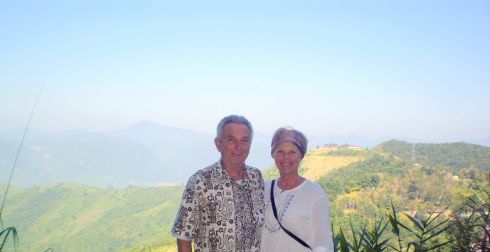

Not long after I returned home A emailed me from Singapore. I’d no idea he’d planned to be in Singapore when I left him in Sydney, but I learned how to do geographicals from him so it shouldn’t have been a surprise. Meet me in Thailand, he wrote. My life is stupid without you. I’ve transferred the frequent flyer points to your account. Don’t argue, please. Don’t turn your face away from me. Meet me in Chang Mai. We’ll go down the Mekong to Luang Prabang, like we always said we would…

I didn’t want to go. I’d done a lot of hard work separating myself whilst in Mexico. I thought I was getting closer to being over it. I knew that if I was ever going to have the life that I wanted, I had to walk away. Twenty years are long enough to try to work things out.

But I went.

It was unspeakably horrible. There is little worse than travelling down the Mekong in a long-boat without seats, crouched on your backpack beside a man you’ve been married to for twenty years who made passionate love to you the night before but in the morning, can hardly bring himself to talk to you. I listened to music on my headphones. I listened to the Brahms & Mendelssohn cello concertos, over and over and over. I’m listening to them now, as I write this. To this day, I can’t hear a cello without a tempest of feeling starting up in me.

I have a photo A took of me standing on the desolate, windswept airstrip in Northern Laos that was used by the Russians during the Vietnam War to supply arms to the Viet Cong. In the background the denuded hills, stripped of their fecund jungle by US chemical warfare, and all these years later, still not healed. In the foreground, a woman, grimly enduring the worst loneliness of her adult life.

We kept going through the whole damn trip and I have no idea why I didn’t just catch the first plane home, except I was too crippled by misery to take any positive action on my own behalf. Every time we made love, and inexplicably, we continued to make something, I did so in an altered state of anguish so intense it acquired a kind of sublimity. Knowing that though it was so finished I was still unable to refuse his touch, indeed, I wanted it as badly as I ever had, made me feel as debased as any addict begging on the street for enough money to get me a fix.

When I left him at the airport in Bangkok I knew without doubt it had to be the end.

Grief expresses itself very physically in me. I have to howl. I have to wail. I have to curl in a foetal ball on some dirty floor somewhere. I can’t care about what I look like, or brushing my teeth, or changing my socks or washing my hair. I can’t eat. I can drink, which does not, in the long run, help at all.

Eventually, after a long, long time, I started on my new life without him in it. I achieved ambitions, enjoyed my family, and my friends. Yet sometimes, compelled and not understanding at all by what, except the most pathetic, abject longing, I wore my wedding ring. I met potential lovers, and quite soon realised that if I expected to be in circumstances in which that might happen, I put on my wedding ring to make sure it didn’t. Desire abandoned me, a lost cause. I threw myself into my celibate life and got so used to longing, I didn’t even notice I was feeling it anymore.

I even managed to conduct civil encounters with A, in places such as the Botanical Gardens and Bondi cafes, and when he touched me, kissed my lips or took my hand, I gently removed myself from him. I could have gone home with him, back into our bed, I felt the stirrings, I knew I wasn’t entirely dead to passion, that I could go there with him again, but I knew I’d likely die as a consequence, one way or another.

I spent many weeks at his side, after his stroke. He knew me straight away. I fed him, wiped the dribble from the side of his mouth that doesn’t work anymore, held his hand while he alternately raved and cried, licked up his tears with my tongue. One day, as I leaned over him to adjust his bed, his good hand found the buttons on my shirt and struggled to undo them. I realised what he wanted, and did it for him, releasing my breasts so he could touch them again. He closed his eyes and fondled me, moving his hand from one breast to the other, as if amazed there could be two of them. I felt no sexual desire, rather an overwhelming desire of another kind: to give him this pleasure, this comfort.

For a couple of weeks, he would signal for me to give him my breasts at every visit. I wore clothes that made this easy, and discreet in case we were interrupted. And then he grew too tired. He began to slip away into another place where I couldn’t be. He still knew me. He just didn’t have the strength to care anymore.

I said goodbye to him, as I knew I must. I sat with him for a long time on our last day. He slept through much of it. Once he woke enough to stroke my face.

I won’t go back. There’s nothing left for me to do there. I always wanted him to die in my arms, or me to die in his, but that was never one of his desires.

I’ve put my wedding ring away now. For such a long, long while I couldn’t contemplate desire. I had to keep it far away from me, I had to hold up the palms of my hands to keep it at bay, because desire only meant him, and saying its name reminded me only of the loss of him.

As I finish this, I realise I have listened to the Brahms & and the Mendelssohn concertos over and over again this morning, and it has been all right. This morning, a momentous one in my life, I’m looking at the time we had together, A and me, and wish I could have learned sooner how bad it was for me. I wish I hadn’t lost so much of my life to something that was never going to be what I wanted. I wish I hadn’t squandered so much love, and so much effort, trying to make something that simply could not be.

Although it was never his intention, the man who showed me how to be a scholar, thrilling me with his intellect; the man who guided me into sexual desire, thrilling me with what he showed me I could feel, that man also, quite inadvertently, taught me how to I want to love, and be loved. Though that love was never to be realised with us, I see today, at long last through clear eyes, that it is A’s greatest gift to me.

Dance me to the children who are asking to be born

Dance me through the curtains that our kisses have outworn

Raise a tent of shelter now, though every thread is torn

Dance me to the end of love *

*Leonard Cohen, Tonight will be fine

*Leonard Cohen, Dance me to the end of love

Tags: Love. Loss. Grief

Recent Comments